Beauty, Goodness, Truth

& Friendship in Christ

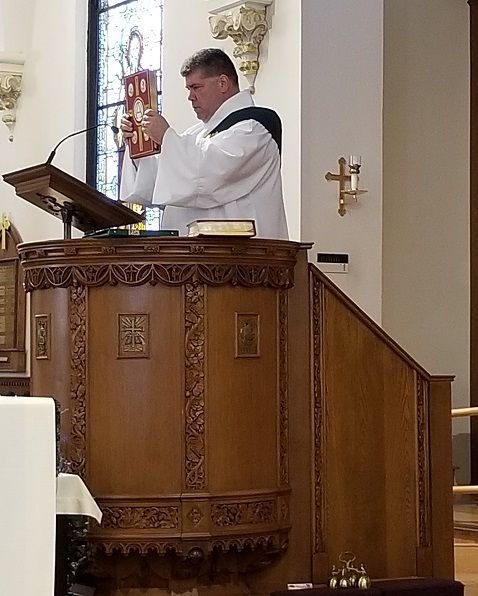

Welcome to St. Patrick Parish

St Patrick Parish welcomes all new parishioners. We are happy to have you worship with us. Please stop after Mass and introduce yourself to our staff. If you would like to register with our Parish, please complete the registration form online, or print out a copy, fill it out, and mail it to the Parish Office or drop it in the collection basket.

Latest from Pastor’s Notes

By Fr. David Barnes

•

March 4, 2026

On Sunday March 22nd, Archbishop Henning will be coming to St. Patrick Parish to offer the Noon Mass and will join us for a reception afterwards. His office called several months ago and expressed the Archbishop’s desire to visit us and celebrate Mass with us. Archbishop Henning is our shepherd and he desires to know us and it would be good for us also to know him. Please make an effort to join us that day for the Noon Mass. This weekend begins the Catholic Appeal. I will speak briefly at all of the Masses asking you to join me in supporting this important effort. The Catholic Appeal provides support for Archdiocesan ministries that provide invaluable support to all parishes throughout the Archdiocese. Every parish in the Archdiocese is required to meet its goal. I would be grateful if we could meet our goal quickly! Please make your pledge today. Before asking you to make your pledge, I have already made my donation. Please join me. For the next several Sundays the Gospel passages we hear will come from the Gospel of St. John. They are lengthy passages that are extraordinarily beautiful and deeply moving. These scenes from our Lord’s life really help us to encounter the Lord in a more profound way. If we take the time to pray with these passages during the week, we cannot help but be drawn more closely with the Lord. We will not simply hear these accounts read to us. We enter into these encounters. This week we are there when Jesus encounters the woman at the well. Next week we enter into the encounter of Jesus with the man who was born blind. The week after that, we stand with Martha and Mary and all the others who were there when Jesus raised Lazarus from the dead. Although each one of these Gospel accounts is filled with innumerable points of meditation, today I want to mention just a single theme that runs through all of them. In each of these encounters the person encountering Christ seems to be in an impossible situation. The obstacle to happiness seems insurmountable. The woman at the well was immersed in a life of sin and infidelity. Her shame was great. She was an outcast and seems to have thrown herself ever more deeply into sin. The man born blind suffered not only from his physical impairment, but also from the judgement of others who presumed his affliction was a punishment from God. And Lazarus, well, he confronted the greatest obstacle of all, death itself. Into each one of these situations, Christ entered in and set the person free; the woman at the well from sin and shame, the man born blind from his affliction, and Lazarus from death. This is who Christ is. He saves. He rescues. He has power to overcome what appear to be definitive obstacles to happiness. I know that I speak and write often about the Sacrament of Confession. That is not to place a burden upon you. It is just the opposite. It is because in this great Sacrament, the Lord enters into what seems an impossible situation and he sets us free. The same Jesus who entered into the lives of these suffering people in the Gospels, he is the same Jesus whom we encounter in the Sacraments. We can be free. Freedom is not trying to ignore or suppress our past sins. If you have any conscience at all, these things will always resurface. Past sins tend to blackmail us. They whisper to us that we will always be the person that did “such and such.” Present sins paralyze us and blind us to the love of God. Since they are freshly committed, we are tempted to wait until “some future time” to confess them so that we can feel better when we say, “Well, that was not recently.” (The problem is that when the future comes, we are still ashamed and, in the meantime, we only grow worse.) These obstacles stand in the way of moving forward in our life. Does Jesus want this for us? Absolutely not! Just as he entered the lives of those three individuals and set them free, so Jesus–our Good Jesus–seeks to enter our lives and set us free. The whisper that your past sins are a permanent disqualification from a life of grace is a lie. The whisper that your sins are an insurmountable obstacle that defines your worth is a lie. All lies. In the confessional, we encounter the gentle Jesus. In the confessional, we encounter the Jesus who overcomes the shame, the blindness, and the death that sin always brings. In the confessional, we encounter the Christ who lifts up, who gives sight, and who restores life. No sin has more power than Christ. In this Season of Lent, I encourage all of us to have recourse to this great Sacrament. Jesus loves you and desires that every obstacle in your life be removed by Him so that you can be free. He is Lord. He can do it. Your Brother in Christ, Fr. David Barnes

Mass Times

Weekend:

Saturday Vigil: 4:00 PM

Sunday: 8:00 AM, 10:00 AM,

12:00 PM & 6:00 PM

Weekday Mass:

Monday - Saturday: 12:00 PM

Held in Lower Church

Confessions:

Monday - Friday: 11:20 AM - 11:50 AM

Saturday: 3:00 PM - 3:45 PM

Held in rear of Lower Church